Big secrets

In search of the big secrets

Science is shaped by researchers working in many different disciplines. One of the most important components is humans’ natural curiosity – the desire to learn and to understand.

Particle physics deals with the smallest building blocks of matter and how they influence each other. A common view of the physics behind this microcosm is necessary in order to understand all natural processes.

To learn about these smallest of building blocks, we need large particle accelerators. These use particles which we know about to create new ones which were previously unknown to us. Huge detectors are used to identify and measure these particles with great accuracy. Every second, billions of particles have to be detected and measured, even though they are often present for only fractions of a second. This requires state-of-the-art technology which in many cases does not yet exist and therefore needs to be developed. Such research enables us to expand our knowledge about the smallest building blocks of the universe. This knowledge can also be used in other areas, for example in the field of medicine to develop new ways of treating patients.

Big Data

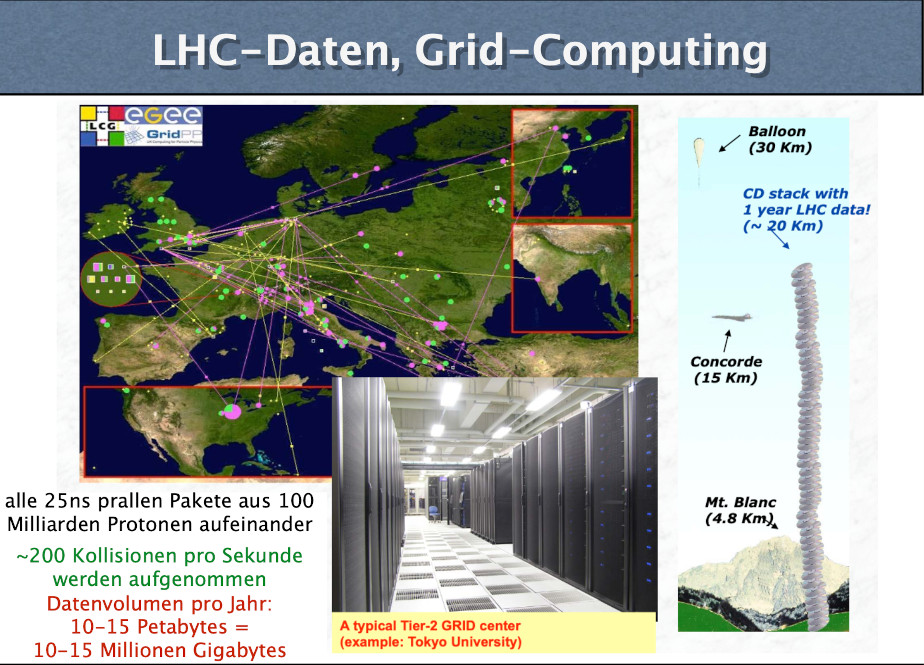

At the LHC, packets of 100 billion protons collide every 25 nanoseconds – that is 40 million times per second. Of these, about 200 collisions are recorded per second. In one year, this results in a data volume of 25 petabytes, or 25 million gigabytes. This corresponds to more than one million DVDs per year.

This flood of data is analyzed by thousands of scientists around the world – an enormous challenge in terms of data storage and computing power. The Worldwide LHC Computing Grid (WLCG) involves more than 170 computing centers in over 40 countries. It executes more than 2 million computing jobs daily, and global transfer rates have regularly exceeded 60 GB/s at last count. These numbers will increase over time as computing resources and new technologies become more available worldwide.

DESY operates a so-called Tier 2 center across sites in Hamburg and Zeuthen, which provides large computing and storage systems for the LHC experiments.

Particle accelerator

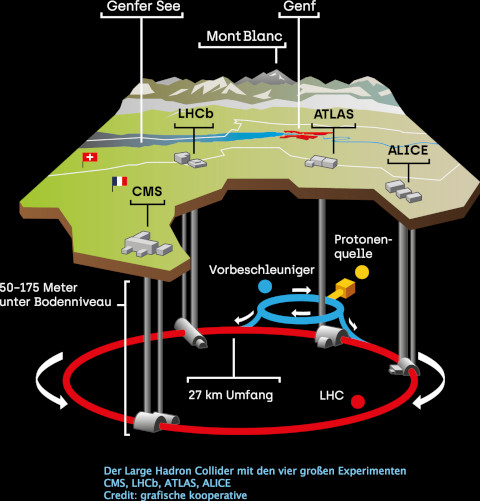

As Einstein's famous formula E = mc2 shows, there is a direct relationship between energy and mass. This principle is used in particle accelerators, where particles collide at very high energies to produce new, heavy particles. The largest and most powerful particle accelerator in the world is currently the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN.

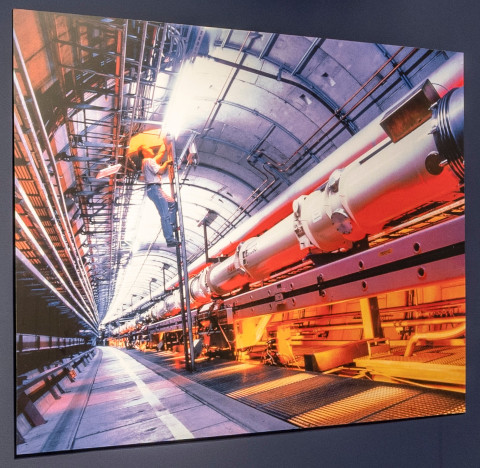

The LHC is a circular accelerator. Protons are accelerated around in a circle in order to gain energy, almost reaching the speed of light. Magnets are used to keep them on the right trajectory. Particles are accelerated in the opposite direction and made to collide at certain points. These four points are the four major experiments. Because of the high energy levels, the particles do not simply bounce off each other. Instead, they are transformed. The energy that is saved in the movement can be released and turned into mass by the collision. This makes it possible for new particles with an even higher mass than the original particles to be created.

Circumference of the accelerator ring: 27 kilometres

Location: 50 – 175 metres underground

Magnet operating temperature: –271.25 °C

Particle collisions: 40 million per second

Particle speed: 11,245 laps per second (almost the speed of light)

superconductivity

Electrons conduct current transport through electrical conductors. However, this does not occur without losses. The heat generated corresponds to the friction of the electrons in the metallic conductor. At very low temperatures, however (approx. below -260°C ), such metals abruptly change to a superconducting state and the electrons move through the conductor without friction or loss. This effect was already discovered in 1911. It was not until 1957 that the theory for describing it was found, based on quantum theory: from a certain transition temperature, pairs of electrons (so-called Cooper pairs) form in the conductor, which can now move together through the conductor with the lowest possible energy (i.e. in the ground state). The electron pairs guide each other through the conductor, so to speak, and thus prevent any friction with the other electrons and ions.

superfluidity

Superfluidity is a phenomenon that occurs in liquid helium: at about 2 degrees above absolute zero, i.e. at about -271°C, liquid helium can flow virtually frictionless through the tiniest capillaries. When a glass vessel is immersed in a container with superfluid helium then the helium does everything to bring the liquid level in both containers to the same height and even flows up the walls!

With this property, liquid helium stands out as an ideal coolant that quickly and uniformly conforms to the materials being cooled.

To explain this surprising property, one starts from a two-fluid model, where helium consists of two parts at the same time, one normal and one superfluid. On the quantum mechanical level, this property is explained by Bose-Einstein condensation, according to which, above a certain temperature, the helium atoms can all go to the same lowest ground state and, so to speak, no longer feel any friction.

CERN – research bringing people and nations together

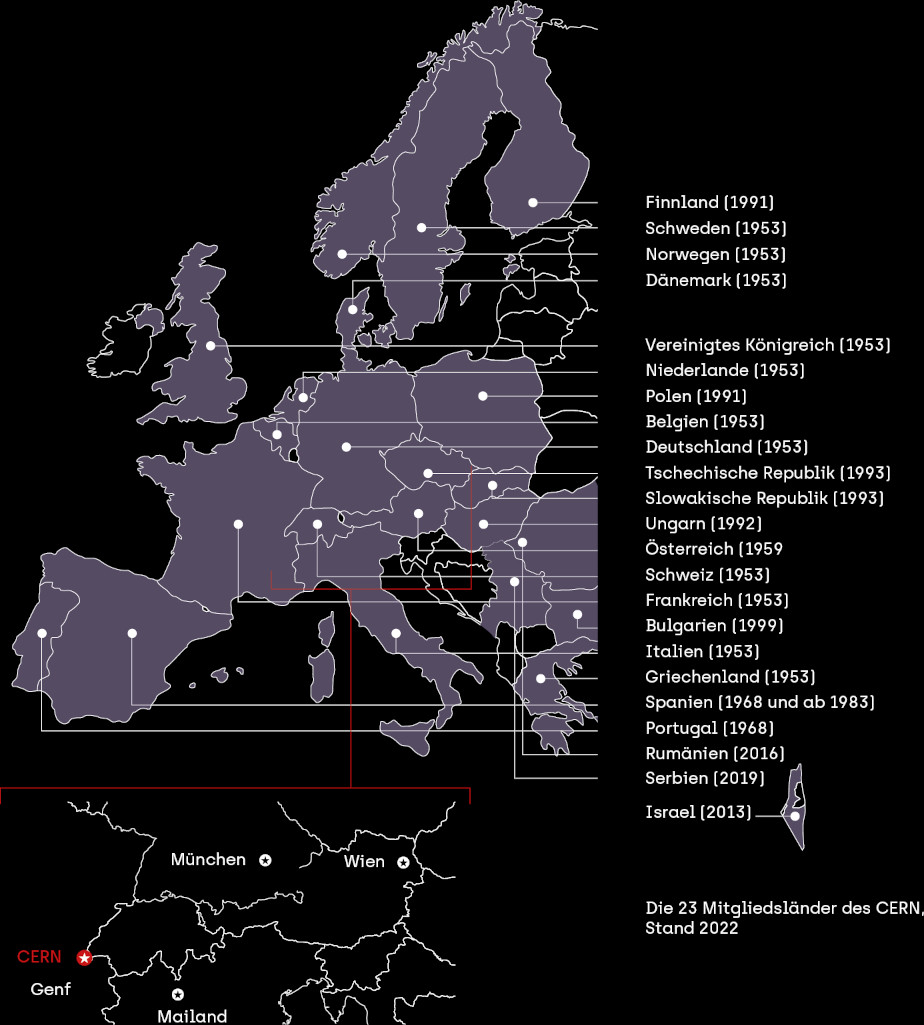

The European Organization for Nuclear Research (Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire, CERN) is the world’s largest and most important centere for fundamental research in the field of particle physics.

It is located on the border between France and Switzerland, near the city of Geneva, and is an international organization like the United Nations.

Its task is to carry out research into the fundamental laws of the universe. CERN develops and builds complex research infrastructure such as the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) and makes it available for scientific experiments. CERN gives researchers of all nationalities the chance to work on scientific projects aimed at generating new insights as well as the opportunity to exchange their ideas and knowledge on these topics.

Founded: 1954

Germany is a founding member and today the largest contributor.

Number of member states: 23

Number of employees: around 3,400

More than 17,000 scientists from universities and research institutions in over 100 countries carry out research at CERN.

Sensitive giants

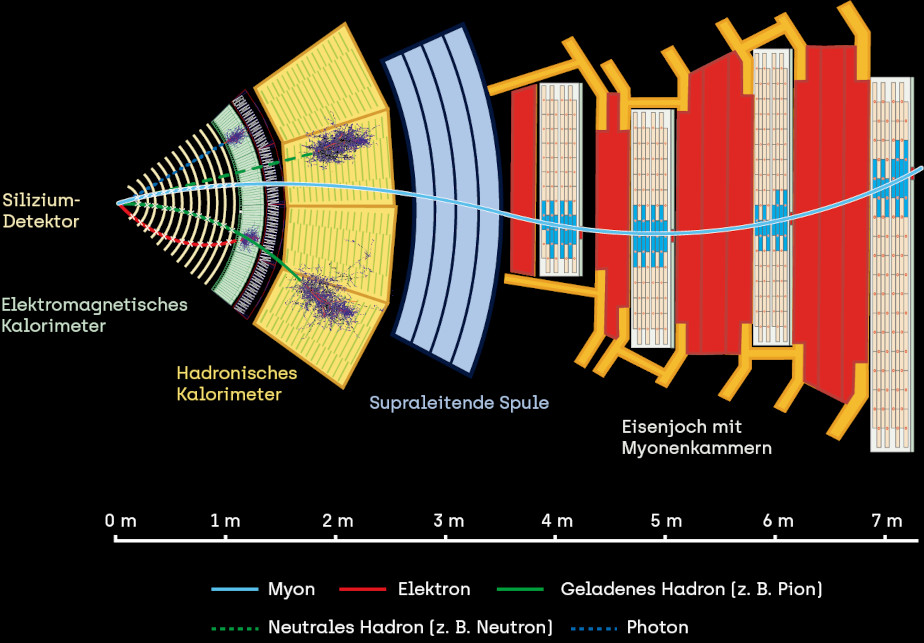

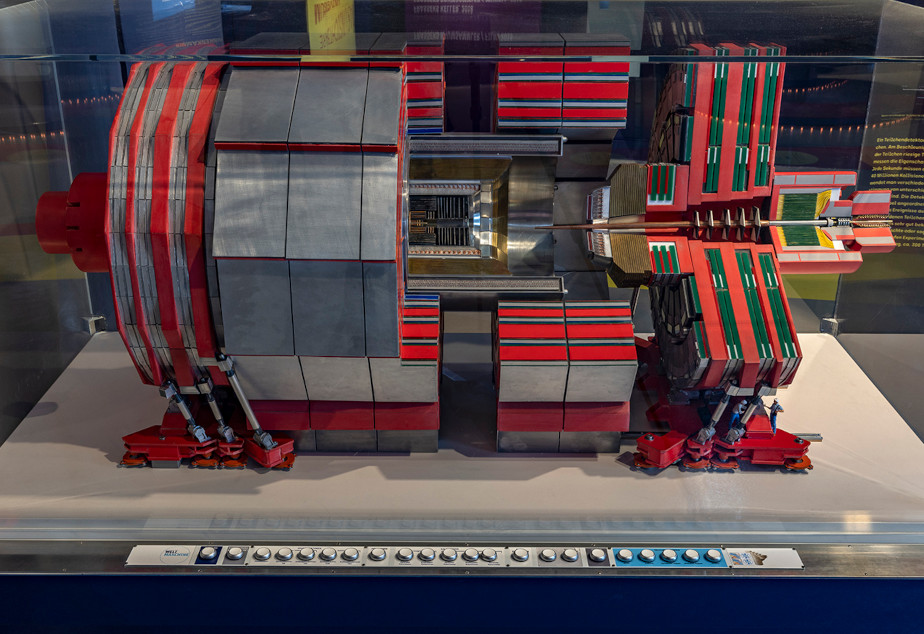

A particle detector is a device used to measure particles.

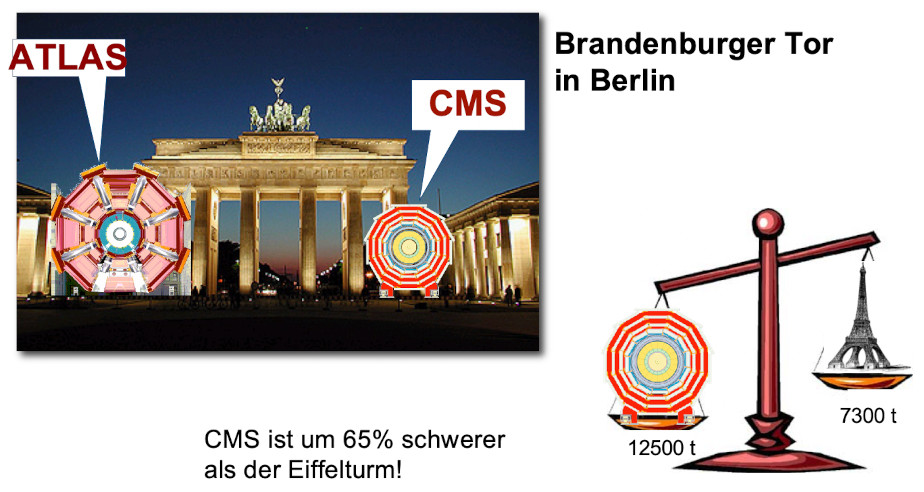

Huge particle detectors are constructed at the accelerator in the area around where the collisions occur. These measure the properties of the newly created particles. Every second around one billion particles created by almost 40 million collisions have to be measured. This requires a range of detector systems, with each system designed to measure certain properties of the particles. The detector systems are organized like the layers of an onion and record the collisions between particles as events. Most of the newly created particles are already well known to the researchers. Only rarely do less well-known or even previously unknown particles occur. That is why experiments like the CMS experiment run 24 hours a day for around 300 days a year.

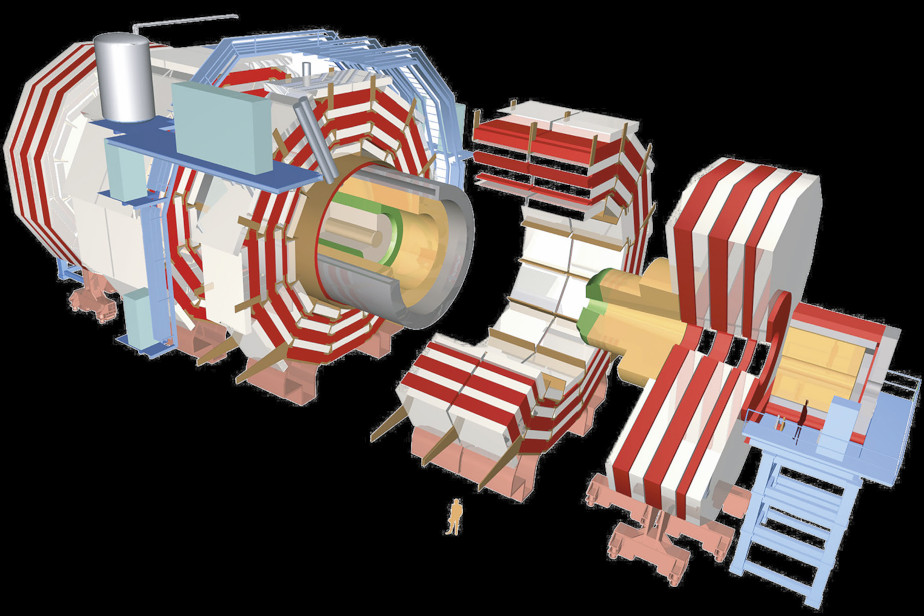

A view of the CMS detector at the Large Hadron Collider

Size of CMS

Proton soccer

Collision course

Try operating the particle accelerator

Selfie spot

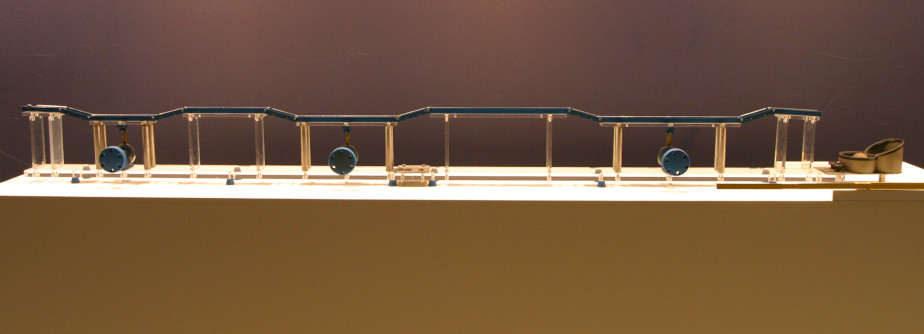

The HERA accelerator lies beneath the houses, gardens and parks in Hamburg Bahrenfeld. Its tunnel is 6.3 kilometres long and up to 25 metres deep. HERA was in operation until 2007 and was used primarily to research the nature of the proton. Today, it is part of many DESY guided tours.

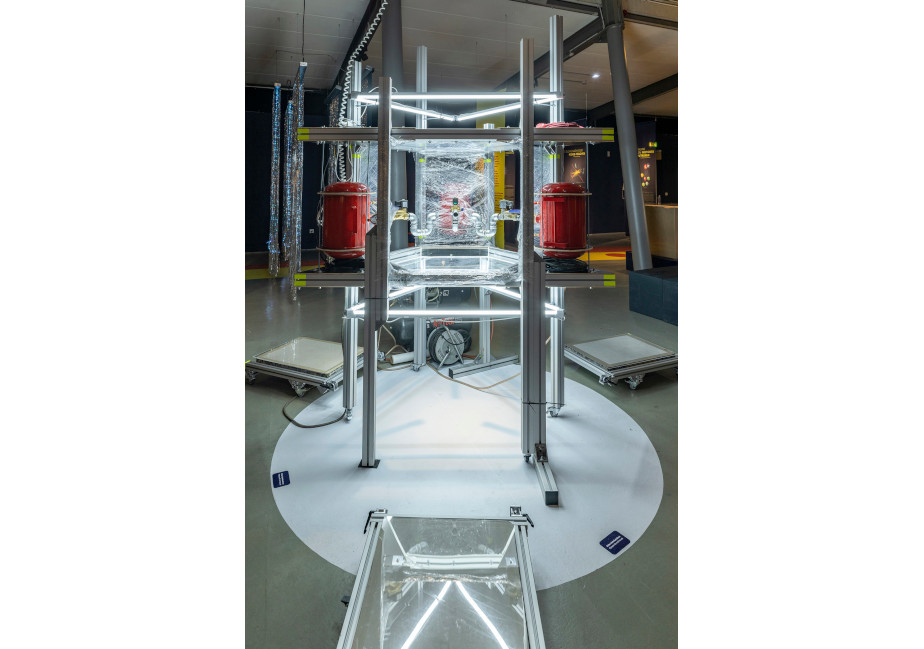

Marcel Grosse

Accelerator3 (2022)

Scientific procedures form the basis of Marcel Große's open-ended artistic experiments. In his experimental set-ups, he employs a wide range of materials: from devices derived from laboratory contexts, to plumbing supplies, to compressed air tanks used in vehicle production. The latter are also components of his latest construction, Accelerator3, which is inspired by the apparatus used in particle physics to simulate the cosmic Big Bang and to measure dark matter. In Große's work, however, the associated particle collision at top speed follows its own unpredictable system: three compressed air tanks facing each other are simultaneously discharged in a closed compartment. The resulting pressure wave disperses ink particles, which collide here with lithographic stones. Analogue prints replace digital recording methods: a cooperation with the museum's lithography workshop. In his sculptures and spatial installations, Große seeks to make processes visible. Invariably, he thus incorporates the element of surprise in his works, embracing possible failure. Analogous to methods of research, the artist's guiding principle lies in productive deviation: in the exception that creates new rules.